- Published on

Plastic Flowers by a Poisoned Well: Could a Simple Script Change Fix Poppy Playtime?

- Authors

- Name

- Katie Quill

Word Count: 4000

Reading Time: 30 Minutes

I don’t like when people write fanfiction. Wait, let me back out of that noose. I like when people write stories based on media they enjoy. What I dislike is seeing people sit down to critique, analyse, or review a piece of media but fill their script with headcanon and things that would have “fixed” the problems it has. They’re writing fanfiction; when I was younger, these were called “fix-it” fics, though I haven’t heard that term in a while. Stories like this can be fun, but when injected into a critical essay, the actual qualities of the thing being analyzed often end up on the cutting room floor.

People really want to rehabilitate Harry Potter, is what I’m saying.

But I think I can fix Poppy Playtime. I see the vision, I understand how the pieces work together, I have transcended the role of critic and become fangirl. So pretend I’ve strapped you to a chair in my basement in front of a chalkboard, because I need to tell someone all my thoughts about this series. You can’t leave; you’re on the honor system. I also soundproofed the walls and told everyone you were taking a personal day.

How Did We Get Here, In My Basement, Anyway?

My very first article was about my mixed feelings on Poppy Playtime and how I felt it fumbled its mystery narrative. I worried the game was struggling with its own identity, and since Chapter 4 released a year later, I thought it would be interesting to revisit the mystery and consider a change that might have ironed out the wrinkles. That first article was written based on some late-night scribbles I made during a hypomanic episode, and while it did give me the push I needed to commit to essay writing, there are some major shortcomings.

Some things I got factually wrong about the game itself. The first chapter was not initially released for free like Bendy and the Ink Machine Chapter 1; that was a later change made to bring on more players. I also said the game didn’t have a PEGI or ESRB rating. It turns out both those organizations have websites where I could have looked the information up directly. I’m just a little stupid, is all.

I didn’t understand the story of Chapters 1-3 as well as I thought I did. It would be easy to blame the game and its FNAF-like storytelling for this, but some stuff would have been more obvious if I’d paid closer attention to recurring names and the content of the collectible tapes. Poppy’s characterization between Chapters 2 and 3 is also more consistent than I assumed, given that she’s in a bad mood after being freed from her kidnapper at the end of Chapter 2. And in hindsight, I don’t know if it’s that big a deal that newer, bigger chapters are more expensive, if only because they come out pretty infrequently. I do hope that when the game is finished, Mob Entertainment does what Bendy did and revamps the Steam page into a single full-priced item.

But I stand by a few things. The gameplay is better than people give it credit for; I appreciate the grabber mechanic as an idea that feels new and overall well-executed. It is much more of a puzzle adventure game (like Portal) than a glorified walking simulator the way Bendy and FNAF: Security Breach were. People hated the puzzles in Poppy Playtime, and I hate walking simulators, so in this we are divided. And I maintain that ARGs and spin-offs are a bad place to reveal important story beats and useful information, especially when the main game is already a paid experience, though Poppy Playtime is less guilty of this than others.

Praise where it’s due, though. While I don’t appreciate the mystery writing, the game is well-paced as a horror experience. Ollie’s introduction in Chapter 3 felt a little forced, but it was ultimately necessary to break up the monotony of the first long chapter. And the game’s environmental storytelling is excellent; the use of VHS tapes in place of audio logs sticks out, but it’s no more silly than anything else in the game and fits the analog horror vibe. If anything, part of me appreciates the game highlighting how silly audio logs are by taking them to an absurd extreme, even if that means it’s still guilty of using them as a storytelling shortcut.

The Challenges of Critiquing a Serial Release

Poppy Playtime is a lot harder to pin down than Bendy was. I have no idea what the developers are planning until they reveal it. It’s easy to condemn something that turns out to be setup for a strong plot beat down the line, which I have. Serialization (separate from sequelization) is a very old concept, but it’s not something we engage with much outside of TV. The design philosophy of a game as a single narrative told in discrete chunks feels alien to me despite having lived alongside it for over a decade now, and it’s hard to know if the things I chafe against are problems with the game itself or conventions that simply don’t resonate with me.

Serial fiction often changes as the creators develop new ideas or respond to feedback. While Poppy Playtime clearly had funding from the get-go, the ability to scale-up development over time has given it a production value unusual for the genre (though FNAF: Secret of the Mimic looks to be challenging it for that crown). It’s easy for a valid criticism—that Poppy Playtime is trying too hard to be Bendy—to become outdated, which is fine if you’re analyzing one chapter but makes it hard to make broad statements with certainty; even a clear trajectory can change with a new installment. There being so much downtime between releases also makes it hard to remember what happened from one part to the next, so character names and plot beats become easily forgotten or misremembered, making it harder to engage with or assess the story.

Something that didn’t occur to me when writing the previous article is that every chapter must reintroduce gameplay tutorials for new and returning players. How do you critique this? Conventional wisdom says it’s bad game design to involuntarily repeat tutorials—you’ve failed to teach the mechanic—but it’s also unreasonable to sneer at it when people might actually have forgotten how to play in the downtime. I don’t have a satisfying conclusion to draw.

The Story So Far, Briefly

In Poppy Playtime, you take the role of an unnamed (but not quite anonymous) former employee of the Playtime Co. factory returning to investigate the disappearance of every single person in the factory one year earlier, spurned on by a blood-stained letter in the mail. Chapter 1 has you turn on the power and discover a giant living toy (Huggy Wuggy) who chases you; escaping him leads you to Poppy, a little talking doll trapped in a glass case. In Chapter 2, Poppy reveals a train to the surface before being kidnapped by another giant toy (Mommy Longlegs). This one can talk and wants to kill you, though some compulsive behavior prevents her from doing it through any means but deadly childrens games. You survive, she does not, blood goes everywhere (confirming these are living beings), and her body is dragged away by a mysterious figure. Poppy is saved and leads you to the train but diverts it to bring you deeper into the factory so you can “save everyone,” only for the train to derail and separate you once again.

If you’ve been paying attention to the environmental storytelling up to this point, as well as collecting the VHS tapes scattered around, you already know about the Prototype and the Hour of Joy, but not what those are. Chapter 3 confirms that the Prototype is what all other living toys are modeled after, that the toys killed the employees during the Hour of Joy, and that the factory was experimenting on orphans in order to surgically transform them into living toys of various sizes. Poppy wants you to kill the Prototype to save the remaining survivors.

The bulk of my critique in the first article centered on the fact I didn’t find the mystery writing compelling. While the moment-to-moment scripting and pacing is fine, even compelling and emotional, it takes too long for the plot to start. Chapter 1 is a perfect introduction, focused entirely on familiarizing the player to the conceit and mechanics with optional foreshadowing. Chapter 2 feels like a massive diversion; just as Poppy is about to fill us in on the meagrest of details, she’s snatched away, and you’re sent through a series of arbitrary tasks that drag the narrative to a stop. As a result, Chapter 3 ends up doing too much to play catch-up instead of fully exploring its own premise, made all the worse by the fact that Poppy decides not to explain anything until the very end of the chapter!

One Minor Major Script Change

I think I’ve made it clear that I don’t like offering “fixes” for the stuff I write about. When people do, they often end up building something so different from the original narrative that any insightful critique is lost. I’m only willing to do it this time because I do believe I see the vision they were going for, and Chapter 4 makes me think some of the ideas I had were meant to be surprise twists anyway. I genuinely believe you could do a lot to fix the weird pacing of the first three chapters by only tweaking the dialogue of a few scenes; no adding or subtracting story beats, mechanics, or level design.

As of Chapter 4, we don’t know for sure who sent the note that lured the POV character into the factory, however the most likely candidate is the Prototype himself. That may turn out not to be the case, and if so, this “rewrite” falls apart, but that caveat is the only thing I can think of that might make my idea incompatible with the story we got.

Chapter 4 implies Mommy Longlegs was working for the Prototype, something not clear from her own dialogue, and I propose we just make that explicit. Have her acknowledge his existence, praise and defend him, condemn Poppy for trying to interfere with his plans. Making her the vector through which the player learns the most basic details about the Prototype takes pressure off Chapter 3 to lay the groundwork, giving it time to focus on the interesting things it introduces: Catnap’s surreal reverence of the Prototype, the red smoke, victimizing orphans, implications about the true identity of the Player Character.

By formally introducing the Prototype early in Chapter 2, we do a lot to eliminate the feeling of that installment being purely filler. Mommy Longlegs can drop hints about things that will be expanded on in Chapter 3 by taunting the character (whom she already does recognize in canon), and her openly being an agent of the Prototype makes slowing you down feel “part of the plan” instead of “written as it went.” The player can infer that Huggy Wuggy wanted to kill you for the same reason instead of assuming, based on the game we did get, that these two were simply rogue elements.

Falling action for the chapter could also be beefed up significantly. This right here is the change that I think strays the furthest from the developers’ actual intentions for the Prototype and his plan, but I believe it would drastically improve the game as a whole. Poppy would reveal that the Prototype sent you—the surviving Playtime Co. employee—a letter to lure you back in order to lift the lockdown keeping the toys trapped. Mommy Longlegs only needed to stop you from reaching the train so the Prototype could finish making preparations before it escaped to start abducting children from the outside world. In Chapter 2, we don’t know that children are being experimented on, so this creates intrigue, and confirming that the Prototype tricked us makes the player feel taken advantage of; now we have a personal grudge against the Prototype, not to mention a feeling of responsibility to end this ourselves because our actions put more children in danger.

In our alternate series of events, Poppy doesn’t immediately decide that she needs you to save everyone at the end of Chapter 2, instead derailing the train herself to stall the Prototype for as long as possible; without the train, he needs a new plan to reach the surface. She can then apologize for this in Chapter 3 and conclude that the player alone may have the determination to stop the Prototype for good, judging by how well you handled Mommy Longlegs and Catnap. Though she’s stalled the Prototype, there isn’t much time before he adapts his plan to the new circumstances, and she can’t kill him herself.

I’ve heard it said that writing a story is about making decisions that work together so well, it feels like there was no other way it could have played out. With Chapter 4, I’m not one hundred percent sure the Prototype did send the letter; we’ll have to wait and see. The real goal for this reinterpretation of events is to create a gently increasing sense of tension that the current game lacks. Chapter 2 feels like filler except for a teasing confirmation of the Prototype’s existence, but even that was foreshadowed in Chapter 1. If Chapter 1 had seamlessly transitioned into Chapter 3 instead, the plot as it currently exists would not need to change. By having the derailment hinder the Prototype’s plan, establishing a back-and-forth dynamic between the Prototype and the hero, and by having Mommy Longlegs give important exposition that furthers the mystery and intrigue, we make Chapter 2 feel necessary.

So... Chapter 4

I’m so many months late to this article that I may as well talk about Chapter 4 now so I don’t have to do it later.

For all its flaws, Chapter 4 is possibly the best (and definitely my favorite) so far. They took their time to make something that looks gorgeous, feels tense, and is loaded with both story and plot progression a way the prior chapters simply weren’t. The prototype feels truly threatening, and the theme of how desperation breaks people down into their worst selves is oppressive. Even though the cliffhanger lingers a bit too long, it feels earned; this is the most emotionally loaded moment in the game so far. Finally we have an installment of Poppy Playtime that doesn’t feel like it’s just cashing in on Mascot Horror but is actually trying to be its own thing.

It’s far from perfect. You’re hit with a lot early on: hills of dead bodies, an underground prison complex, story elements that feel like they come from nowhere. It strains the suspension of disbelief in a way not even the underground orphanage did. While I appreciate the game going full B-movie horror with this chapter, I still wonder what the philosophical motivation for this place is. Elliot Ludwig wanted to discover eternal life through the poppy flower, but for a mystery story, I’m stumped as to how children can be surgically transformed into living toys on the scale of a meat-packing plant without being discovered. No single orphanage can account for human trafficking on this scale. Outlast did this much better by keeping the operation small enough that a whistleblower was caught immediately. The sudden increase in horror also reaffirms my confusion over who this game’s intended audience is. And while there is something to be said about the way children are routinely dehumanized and objectified by adults who see them as assets, the game doesn’t seem to be making a statement about it.

I’ve been watching a lot of the YouTuber Night Mind recently, and something he loves in unfiction projects is when the fiction itself answers “Why is this even happening?” If it’s a found footage series, why was someone filming at all? Chapter 4 is the first time the audio logs actually have in-universe characters question the operation, who benefits, and how they can live with themselves for participating. In particular, the tape of Eddie Ritterman is intense, giving serious insight into the cult-like mindset of the higher-ups in the company that make decisions like demanding an underground prison complex more believable.

My favorite thing about this chapter, though, is that the storytelling and characterization have taken a huge step up. When Doey and Poppy are reintroduced to each other, Doey is concerned for Kissy Missy’s well-being, and Poppy insists that she needs to be taken to get help. Doey asks if that’s “for the best,” but before he can elaborate, Poppy gives an almost imperceptible shake of her head to silence him, and he complies. This is the first time anyone has felt like a fully fleshed out character to me. I complained about Poppy not sharing what she knew in previous chapters, and Chapter 4 fixed that by making characters coy with you, because they don’t fully trust you, in a way that comes across in their dialogue and body language. Both Poppy and Doey have believable motivations that leave them in conflict with each other but united against a common enemy. And it’s clear that the other critters in Safe Haven, the only ones remaining who haven’t lost their sense of identity, distrust Poppy after such a long absence, and she is in no hurry to tell anyone what happened to her.

There’s so much I could go on about. The puzzles are more strongly incorporated into the environment, something I didn’t have a problem with but got fixed anyway. The pacing is slow, but there’s always something happening that makes sense given the setting and characters. Foreshadowing is strong, and the mechanics for the boss fight were more effectively established in this chapter than the last one. They even managed to find a new way to evolve the Grabber.

Likewise, there’s a lot I can criticize. I don’t like forced stealth sections in any game, and the fight against the “Endos” in the dark maze is agonizing just to watch. The toys in Safe Haven don’t actually talk or act like children despite not having lived in an environment where they would learn to speak like adults. And while the payoff for Ollie is very good, he feels like a vestigial burden for most of the chapter now that there are other characters to interact with.

But for all the problems, by the end of Chapter 4, I finally feel emotionally invested in where the story is headed and what’s going to happen to these people.

Cursed to be The Contrarian Voice in The room

The most “straight for the throat” criticism I’ve ever received is that I simply have to provide a contrarian response to any opinion. From my own mother, no less! And as much as I’d love to prove her wrong, sometimes I do feel locked against the grain. In this case, it’s less that the tides are turning against Poppy Playtime—the people who like it still do—but there is definitely a change in the wind. Fewer people have nice things to say, more people have thoughts about its shortcomings.

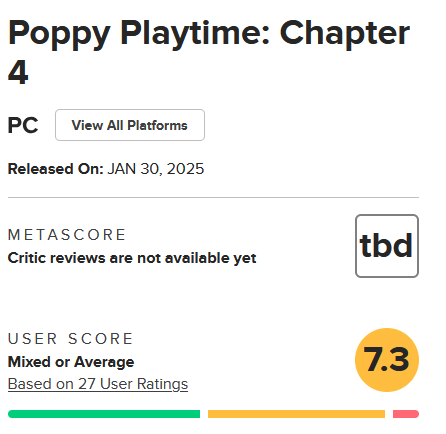

I don’t often seek out critical reception for games I’m interested in. Like many people, I feel traditional games journalism is mostly page filler to make space for ads. For Chapter 4, I only really found a few articles from websites I’d never heard of and a puff piece from ScreenRant. Metacritic doesn’t even give the game a critical score five months after release. Most of the pushback is from laypeople.

Poor performance is the big one. I’ve seen it suggested that a desire to get a game out twelve months exactly after Chapter 3 meant there wasn’t enough time to finish, playtest, and debug. Game-breaking glitches made Chapter 4 nearly unplayable on release. Personally, I can enjoy the story regardless, but as the chapters get bigger, they perform worse, and that’s a damning criticism. There’s no excuse for this trend of releasing badly broken games to the market and asking for time to finish once the money has already exchanged hands; make smaller games.

But I do also see people repeating a mistake from the backlash against FNAF: Security Breach and Cyberpunk 2077. They will call the game badly designed at the start of their YouTube video or blog post, spend most of their time describing bugs that clearly weren’t part of the intended experience, then rush through their opinions on why the game is also badly designed with very little supporting evidence. It’s actually embarrassing. I’ve seen very solid critical dissections of both those games, but I sympathize with the people who ask, “Can you please shut up about the glitches? We get it!”

The YouTuber Artrodius released his own review of Chapter 4 that is frankly more insightful than anything I came up with. He summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of the chapter well: It has the highest highs of the series so far, but also its lowest lows; the devs bit off more than they could chew, and the chapter would be drastically improved by cutting the fat and polishing what remained; it will not convert anybody into a fan, but it is a rewarding instalment for those who are. He understands the appeal of Poppy Playtime better than I do, and his criticisms are much closer to the bone than the long rambles of people who want an easy target from a maligned game, genre, and company.

Inna Final Analysis

I don't really know what this article is, much like how I don't really know what to make of my last article on Poppy Playtime. This game just does something to me and my ability to structure a coherent narrative thread. I like the game, and not ironically despite its flaws or cynical corporate nature. YouTuber CheeseYeen recently said something similar about FNAF: Security Breach, a game I have nothing but criticism for: it’s hard to put into words why you earnestly like something bad. He also indulged in a bit of writing fanfiction for that video, hoping to find a way to make the game scary without changing its fundamental design. Meanwhile, the recent commercial and critical flop MindsEye is quickly becoming a favorite among streamers who can’t find anything positive to say but have a blast playing the game. And how many people actually like Bendy and the Ink Machine for what it is and not nostalgia for the fandom?

Hopefully Chapter 5 puts a bow on this game with a satisfying narrative conclusion. (I will be so frustrated if it’s not the final chapter; please let this game end.) I don’t expect that anyone will be able to say it fixed the design problems that plagued earlier entries. Mob Entertainment definitely improves with each new installment, but the flaws are a cumulative part of the game’s identity. Like FNAF: Security Breach, it’s hard to engage with this game without asking “Why did they do this instead of that? That would have been much cooler and made more sense for the story/tone/gameplay!”

I call Poppy Playtime “plastic flowers by a poisoned well” because it manages to thrive despite Mob Entertainment’s terrible business decisions, yet most people will only ever see it for a cheap corporate product pretending to be something else. Personally I find plastic flowers easy to care for. As to whether or not one script change could have “saved” Poppy Playtime: the answer is no, because the people who like it or not aren’t motivated by the quality of the writing. Art is holistic, and it may just be the postmodernist in me, but the canvas and the process are part of the experience. We do serial games a disservice by trying to approach them as just the sum of their parts.

Thanks for reading.

If you want to support a writer with no corporate ties who isn't trying to sell you anything, you can donate as little as a dollar to my ko-fi. You can find more ways to read my writing and follow me on social media here, and I have a Patreon if you like my work so much you simply have to keep giving.