- Published on

Ugly on the Inside, Part 1: Bendy and the Ink Machine's Uncomfortable Relationship with Appearances

- Authors

- Name

- Katie Quill

With Apologies to Pastra

“We all have dreams, ghosts in our past. But those ghosts can give us the path forward.”

Bendy and the Ink Machine (or: BATIM) changed indie horror games as much or more than Five Nights at Freddy’s before it, no question. It cemented “mascot horror” as a viable retail genre and established serialized releases as standard for the scene. With two primary games, endless merchandise, and even several books, it’s safe to say that the series is pretty darn popular.

Chapter 1 of BATIM was released as a $1 demo in February 2017, with additional chapters released periodically as paid downloadable content all the way through… 2018? The steam pages for these DLC have since been removed and the original page revamped. It is now a complete game for $20, which is certainly a more reasonable model for newcomers but also a pain when trying to establish a timeline. Its sequel, Bendy and the Dark Revival (or: The Dark Revival), released in November of 2022 as a full product for $30 and has received a lot of acclaim.

As a demo, Chapter 1 did a good job of hooking audiences on a mystery-driven game with light horror elements. But the scope of BATIM grew over two years, introducing us to lackluster combat mechanics, too many fetch quests, and environmental puzzles that felt like an obligation the developers were bitter about having to include. The story also started to feel more and more like it was being made up as it went along. It didn’t take long for me to fall off the bandwagon when the ride got bumpy.

Yet… people love this franchise. Of particular note to me is the Youtuber Pastra, who released two videos about how BATIM is his favorite horror game and The Dark Revival still manages to improve on it. That’s a huge claim in an era where a lot of good indie horror is competing for praise. I don’t always agree with Pastra, but I genuinely appreciate his insight and positivity.

Some time ago, I came to the conclusion that (excepting hate speech) if even one person likes a piece of media, genuinely or ironically, it has earned the right to exist. I’m going to be saying some pretty negative things about the way these games are written. This doesn’t mean that the dozens of people who worked on these games, or the hundreds of people who worked on the larger franchise, or the thousands of people who are still dedicated fans should feel bad about themselves. The world would not be better if it didn’t have Bendy in it, but there’s still things we can learn from the creators’ mistakes.

Appearances Matter

“I too really believe my characters are more than just drawings. They’re alive. They’re part of us.”

In the Stone Age of the early 2010s, there was a big online kerfuffle about character coding. A lot of people were upset that characters might have depth or symbolism that wasn’t expressed in dialogue; mostly they were angry at people who thought fictional characters might be gay at a time when media companies were a lot more coy about openly LGBT+ characters. The term isn’t a buzzword the way it used to be, but it’s still relevant. Lamenting people not “getting” characters like Walter White or Rick Sanchez—complaining about fans not seeing them as cautionary tales—is talking about character coding: symbolism that informs us of things the characters won’t acknowledge or might not understand themselves.

Whether we idolize or fear Walter White is critical to what we take away from Breaking Bad. Whether we aspire to be Rick Sanchez or pity him changes what Rick and Morty is saying about the behavior of people who decide they’re too smart to listen to others. Whether Bendy is a loveable character brought to life or a demon who terrorizes the people who love him determines if Joey Drew is a genius or a madman.

With the understanding that characters are real people within the narrative but also symbols for larger thematic statements, we have to acknowledge something painful: the Bendy games have an unhealthy obsession with superficial appearances. They reinforce, rather than subvert, regressive beauty standards through the use of characters who are “ugly on the outside” to show that they are “ugly on the inside.” In this franchise, appearance strongly correlates to how much we should trust someone.

This has been a gnat in my soup for a while, but I was pretty hesitant to write about it. My own relationship with the series leaves me too biased to be completely objective; was I jumping at shadows? I managed to find a few former fans of this series—Amber, Jack, and Joe—to see what they thought of my ideas. Each of them brought some interesting insight, and has agreed to let me upload their responses separately so readers can see the full context of their statements.

It’s an inky abyss ahead, so take a deep breath.

Alice Angel

“Only the monsters remained… shadows of the past.”

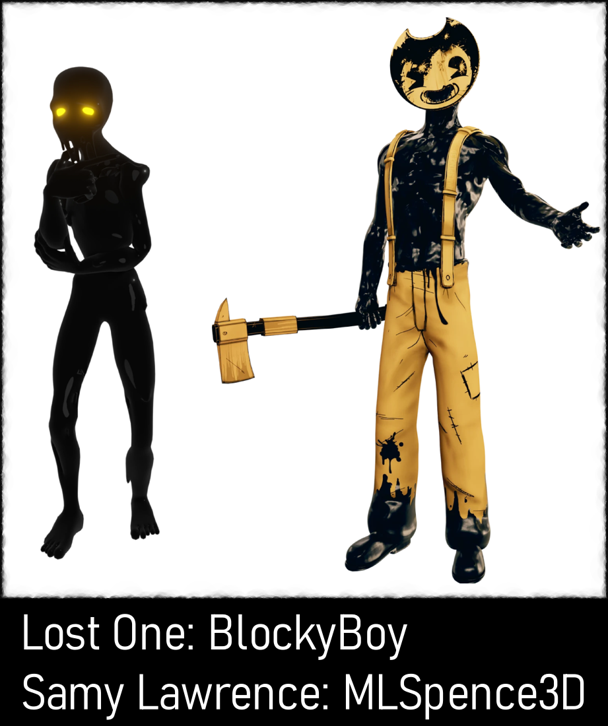

BATIM is set in a run-down 1930s animation studio, so character design draws heavily from rubber hose cartoons. My interviewees agreed that the eerie aesthetics are a huge draw for audiences even if the game didn’t always stick the landing. Jack felt that marketing decisions resulted in many characters ending up “more cool than scary.” Amber appreciated more monstrous creatures such as the Ink Demon (the monstrous version of Bendy that roams the ink world), but others were too generic to be interesting: the inky Lost Ones or man-in-overalls Sammy Lawrence.

The character that resonates the most with players is Alice Angel.

There are two female characters in BATIM: Susie and Allision. For all my spiel about character coding, I don’t want to turn this into “Bendy is secretly super sexist and the creators are bad people and you’re bad for liking the game.” The fact that these characters are women means the specter of sexism is unfortunately hovering nearby, but a game that explores sexist stereotypes or ideas can still say interesting things. If Susie and Allison were male characters instead, everything I want to talk about would still apply.

There are things I am not criticizing BATIM for. I attribute the lack of female characters to limited resources and the way the game was (allegedly) written as it went along. Once the series had the budget to go all-in with The Dark Revival, we saw more women with more screen time and more variety in how they were depicted. Women also work and have worked on the series in a multitude of ways. We can’t say for sure who made what decisions about Susie or Allison as characters, and assigning blame doesn’t help us dissect them anyway, so we won’t try.

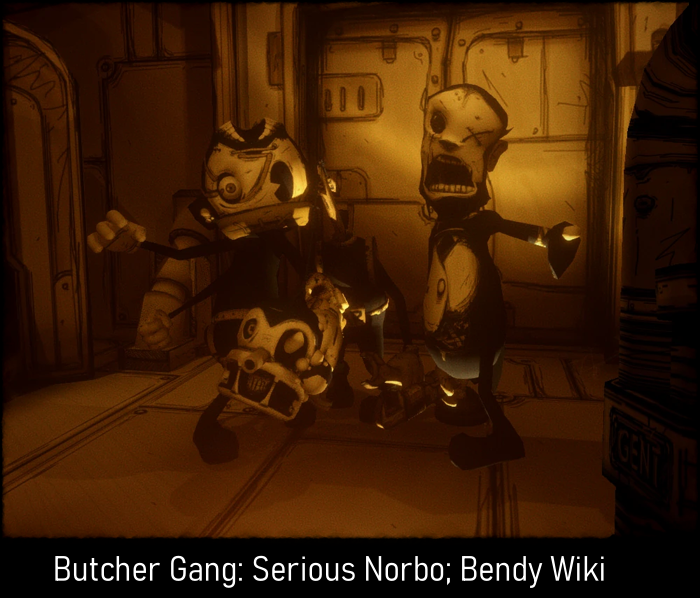

Susie Campbell is introduced briefly in Chapter 2 of BATIM as the voice actor for the character “Alice Angel” and, according to one creator, became so popular with fans that they pivoted Chapter 3 to be about her. Following the pattern of Sammy Lawrence before her, Susie is a villain who was betrayed by Joey Drew and fed to the Ink Machine, emerging as a real-life version of Alice Angel. Amber loves the design, describing it as “interesting and menacing to twist the wholesome angel lady into a Two-Face-inspired design.” Joe agrees: “She is lovely and all that, but you shouldn’t get too close because she is still dangerous on the other side. Compared to the Butcher Gang, who are made out to be fodder, she is depicted as strong.” I personally love that while Susie is loosely evocative of the “femme fatale” archetype, in practice she’s actually a mad scientist experimenting on the other toons.

Unfortunately, Susie has a very sympathetic backstory without being written as sympathetic. Alice Angel was the first character that Susie felt a real connection with as a voice actor, and she had high hopes for her career. Joey Drew, CEO and owner of these characters in-universe, stabbed her in the back by replacing her with the actor Allison Pendle instead. Susie’s own dialogue includes the lines, “[Alice Angel] was beautiful. And loved by all. She was perfect. No matter what Joey says.” He destroyed her sense of self-worth before luring her in to be sacrificed to his machine.

Joey Drew hurt this woman, but that’s all backstory. In the context of BATIM, Susie-as-Alice is a “crazy” villain who seems to bounce between delusions, at times paranoid, other times sadistic and abusive, and sometimes experiencing severe character bleed where she cannot differentiate between herself and the character of Alice Angel. The most notable villain of this game is a mentally ill abuse survivor, and nobody expresses sympathy for her.

“I don’t have much to say about the way she was written beyond: disappointed and perplexed,” Jack told me. “I don’t believe for even a second that the people in charge of writing BATIM noticed what they have done with Susie’s backstory, nor that they care that it is just disgusting.” Jack more than either of the other interviewees believes Bendy as a series to be deeply misogynistic. “I believe that if it weren’t for the fact that her design is… like that, [or] the reason for her wanting to take from other ink creatures [being] to restore her beauty, this could have been a somewhat compelling character.”

I still don’t think this would be less gross if all the characters were male; it would still be a story of someone who suffered constantly at the hands of others being disregarded as inherently cruel. Susie is villainous, but the meaningful difference between her killing ink creatures and protagonist Henry doing so is that she does it proactively and sadistically instead of in self-defense. That’s a compelling villainous foil even without the tragic backstory the creators latched onto her and then ignored. To be clear, I don’t want the takeaway from this to be “never make antagonists victims of abuse”—the cycle of abuse is very real, and in deft hands can be used to tell interesting and meaningful stories—but a backstory cannot be both important enough to smother the audience with and so unimportant that it doesn’t factor into how characters treat each other.

Another topic that risks becoming too much about misogyny is how vain Susie is depicted, but I do think there’s something deeper here than thoughtless sexism. Susie’s primary motivation is not revenge against Joey Drew; she hates him for what he did, but he doesn’t factor into any of her plans. Her primary motivation, the reason she kills and dissects the toons, is to take what is physically perfect in them and make it part of herself. “I just wanted what was promised to me. I just wanted to be beautiful.”

The main form of visual horror in the Bendy series is body horror. When done well, body horror elicits a strong visceral reaction that borders on nausea. Seeing how much harm can be inflicted on the human body evokes both fear and sympathy. This creates a problem for pulp horror such as slasher movies and survival horror games, which use spectacle to create a positive (though still very visceral) reaction to scary elements on screen. Sympathy is traded in for an “Ooh, gross!” reaction accompanied by a laugh.

For the most part, Bendy threads the needle. The Butcher Gang are cartoonishly misshapen—one has their head hanging from a fish pole–in a way that suits pulp horror, and other characters work well as survival horror villains. Susie’s design, however, is reminiscent of more realistic injuries while still being used to shock the player even though, stripped to the bone, she just looks like a severe burn victim. Her on-screen introduction is a jump scare meant to show off how deformed she is in comparison to the cartoon version of Alice Angel, itself more reminiscent of characters like Betty Boop that are regarded as early modern sex symbols. The initial horror of the character doesn’t come from her cruelty or even her mental illness (as trite as that is on its own) but how different she is from the sexy image in our head. We constantly see cutouts of cartoon Alice throughout the level to reinforce this disconnect.

Are vain people evil? The idea that Susie started killing people to make herself more attractive is too shallow a motivation to be believable, trauma or no. In the real world, a lot of people are insecure about their appearances in a way that drives them to hurt interpersonal relationships without meaning to, but it would be cruel to call that morally reprehensible. I think that cruel people care about looking good—physically and socially—because they know it will help them get what they want. A note in The Dark Revival suggests that Susie knows being beautiful will let her move through life easier, but she clearly just wants attention, accusing new protagonist Audrey of “stealing her spotlight.” If they had written Susie as a full-blown narcissist instead of a victim, the escalation from voice actor to serial killer might have felt organic enough for a fictional story.

I wish that the writing on Susie had been much tighter. I don’t want to sit here and write fanfiction, but if they had fleshed out her rivalry with Joey Drew and the idea that her desire for attention came from an undeserved sense of superiority, made the two of them explicitly terrible people constantly stabbing each other in the back for their entire lives, made her the Count Olaf of the series, I think I’d be cheering her on instead of wrestling with mixed feelings. Joe described his interpretation of Susie beyond who she is as a victim: “a person just hellbent on revenge and looking perfect [and not letting small things go], which kind of reminds me as teenagers in a way.”

Truth be told, I like how petty Susie is. I don’t like how they couldn’t decide whether to make her sympathetic or heinous.

Boris, Tom, and Allison

“If you claim your failures are because these things are soulless, then damn it, we’ll get them a soul. After all, I own thousands of ‘em!”

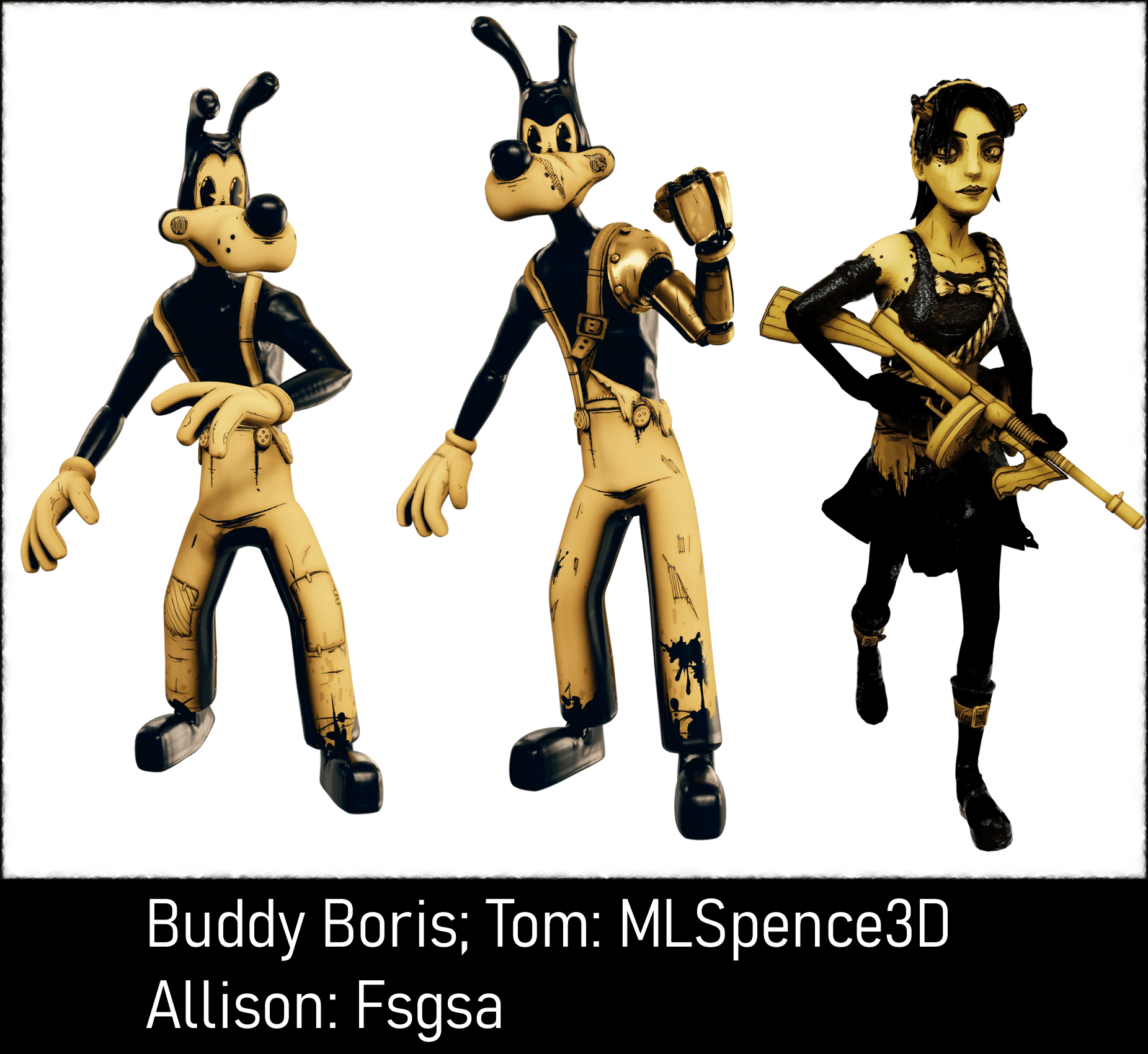

Henry has a number of allies in BATIM. Buddy Boris, Tom, and Allison best show how outward appearance correlates to how kind and trustworthy a character is in this series. Like with Susie, we can’t assume that these are deliberate decisions—too many people work on this series for it to be that simple—but the final result exists independent of the intent behind it.

Buddy Boris is introduced at the end of Chapter 2 as a “perfect” toon Boris brought to life, following Henry through Chapter 3 only to be captured by Susie once the player is sufficiently attached to him. When we encounter him again in Chapter 4, he has been transformed into a Frankenstein Monster to serve as the final boss. This is classic body horror and falls in line with Susie’s mad scientist archetype, but it is notable that when Boris becomes an enemy, his appearance changes from being aesthetically pleasing to being a hideous monster.

Tom is the closest thing to being a subversion of the way beauty in this game signals alliance. He is not a perfect Boris because he has a mechanical prosthetic arm, and while he is mute as Buddy Boris was, Tom expresses antagonism toward Henry through hostile body language. His role as Allison’s protector is used by the writers to create conflict that keeps Henry and Allison from getting along too well. In The Dark Revival, Allison will explain that Tom simply doesn’t trust new people, which is both smart and relatable in a horror setting. I can appreciate that even though he comes around on Henry (for no discernable reason, admittedly), Tom doesn’t have a complete personality reversal where he naively trusts any new person. It just feels bad that he’s the only heroic character to be both distrusting and disabled.

Allison Prendler is the heroic toon version of Alice Angel and the most “normal looking” of all the toon characters, lacking the Betty Boop figure that Alice Angel is supposed to have. She’s also helpful to the player without having explicit goals of her own in either game. I don’t want to be too critical of how she’s written, though. Allison has a very interesting fatalistic mindset, believing in BATIM that she was never meant to leave the ink realm and that it is Henry’s destiny to set them free. The fact that one of the only female characters in the game is strictly there to exposit and support the protagonist bothers me, but her actions do feel in-line with her characterization.

The real problem is her appearance. Not only is she the character least affected by the ink (in BATIM specifically), but she is a deliberately more “realistic” interpretation of what Alice Angel might look like in person. The physical differences between her and Susie could have had a lot of narrative and symbolic weight; as said, sexist stereotypes can still be used to say meaningful things if the writers are clever. People in real life fall victim to predatory marketing or monsters disguised as something people think they want. Here, though, the difference between them seems to be a wink to the audience. “Yeah, Susie thinks that’s attractive. What a loser, right? We know what a real woman looks like.” The fact that the “real woman” in this case is demure and helpful while never needing anything from the player makes the whole thing taste as bad as it smells.

Susie dies in both games; everyone in the ink world comes back to life when the cycle resets. In BATIM, Susie is killed at the end of Chapter 4 when she tries to attack Henry directly. In The Dark Revival, she is killed while attacking new protagonist Audrey. Both times, she is killed by Allison (the woman whom Joey stabbed Susie in the back in favor of) who stabs her through the back with a sword. Only in the second game does Allison speak to Susie, doing her best to comfort her as she dies—the first time in this series anyone is kind to Susie.

Even their rivalry is one-sided. It has to be; Allison is pure of heart, and Susie is uniquely monstrous. You can tell just by looking at them.

End of Part 1

All images taken from the Bendy Wiki